Cancer is big business, make no mistake.

The lifetime risk of developing cancer is now one in two, according to the National Cancer Institute website.[1] This includes men, women and children.

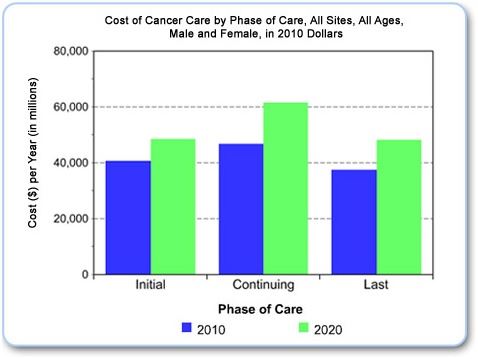

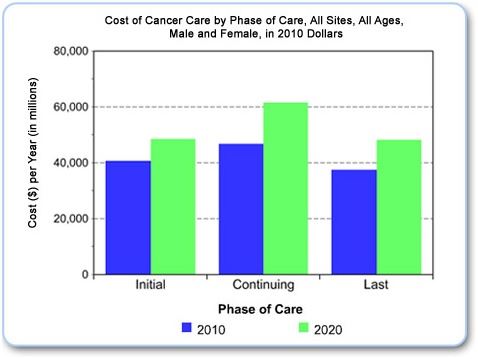

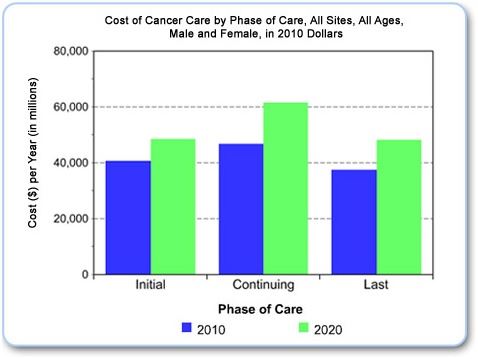

The incidence of cancer is projected by the National Cancer Institute to rise by 30% by the year 2020.[2]

One in four deaths in the United States in 2012 was due to cancer.[3]

The cost of care will, naturally, increase proportionally. Cancer is indeed big business.

Cancer drugs are extremely expensive - $4000.00 per dose for

Herceptin, one of the main drugs used to treat breast cancer - even though it is

only partially effective, and is known to cause life-threatening heart

problems in some patients. $5500.00 is the physician cost for a one month

supply of

abiraterone, a new drug used for prostate cancer.

So why would we want to flush the drugs down the toilet?

An article published in ASCO Daily News during the annual 2012 American

Society of Clinical Oncology meetings in Chicago, IL written by

Mark J Ratain of the University of Chicago, asks just that question.[4]

An article published in ASCO Daily News during the annual 2012 American

Society of Clinical Oncology meetings in Chicago, IL written by

Mark J Ratain of the University of Chicago, asks just that question.[4]

The author’s point is that there is marked variability in absorption of drug, and therefore in its availability to the body, for at least one third of the oral chemotherapeutic agents currently being prescribed.[5] Abiraterone, mentioned above, is one of those drugs. It shows a 10-fold variation in absorption, depending on whether it is taken without or with food, and shows better absorption when taken with a fatty meal.

So why does the package insert and dosing instructions recommend that it be taken on an empty stomach? Because that is what the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends, according to an editorial written in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2010.[6]

In that editorial, the authors (one of whom was affiliated with the FDA)

expressed concern about the potential for high intra-individual variability

in cancer patients resulting from variability in oral intake secondary

to disease or concurrent medications, suggesting a preference for labeling

drugs under fasting conditions, even if bioavailability were markedly

increased by food.

In that editorial, the authors (one of whom was affiliated with the FDA)

expressed concern about the potential for high intra-individual variability

in cancer patients resulting from variability in oral intake secondary

to disease or concurrent medications, suggesting a preference for labeling

drugs under fasting conditions, even if bioavailability were markedly

increased by food.

This author writes: “Although individual patients can have a medication’s dose titrated to the desired effect, it is rarely feasible for an individual patient to adjust his or her dose by administration with or without food to achieve consistent bioavailability and systemic exposure. The volume and timing of a meal, caloric content, liquid content, fat versus carbohydrate content, temperature, and physical composition can all produce unpredictable variability in the magnitude of a food effect from dose to dose.”

Was that perfectly clear?

Translation: patients cannot possibly understand what we mean by a “fatty meal”, nor can they be counted on to consult with their physician if they are unable to consume said fatty meal (presumably because of nausea resulting from other chemotherapeutic agents also prescribed). Therefore patients should take the highest possible dose, with the least effective absorption, in order to be consistent with FDA recommendations - and, incidentally, with pharmaceutical industry profitability.

What a knock! The conclusion of the Jain article questions the FDA’s recommendation: “Drug labeling patterns with respect to food-drug interactions observed with oncology drugs are in contradiction with fundamental pharmacologic principles, as exemplified in the labeling of non-oncology drugs.”

In a word: the FDA needs to put its money where its mouth is - i.e. needs to be consistent with principles of pharmacology, not with principles of profitability.

So what is the alternative?

At the Arizona Center for Advanced Medicine, we use a combination of modalities to treat cancer.

We use diet - primarily vegetable based (to avoid the glutamine which cancer cells use preferentially for their little cancer cell nutrition), free of chemicals and anything which might be inflammatory (sugars, large amounts of animal protein, sodas, chemicals, preservatives, estrogen-mimicking compounds like BPA, etc).

We use lifestyle changes - even a little bit of exercise is helpful to get the energies moving again.

We use alternative cancer-treating medications and supplements - things like high dose ascorbic acid, lipoic acid, DMSO, glutathione, unltra-violet blood irradiation, vitamin B17, and others.

We use energetic treatments to help restore the body’s information systems to their original template.

And we use Insulin Potentiated Chemotherapy, Low Dose (IPT-LD™) to deliver appropriate chemotherapeutic drugs to rapidly metabolizing cancer cells, sparing the normally metabolizing cells in the rest of the body. Chemotherapy is delivered in lower dose, resulting in fewer side effects and higher quality of life than standard chemotherapy, without any decrease in effectiveness.

We do all of the above in an atmosphere of love and acceptance. Each of us brings who we are to the table. Each of us needs to be accepted, with all our good points and all our warts. Only through acceptance and love is change possible.

We all have the chance to love ourselves with all our faults.

The choice is ours.

One in four deaths in the United States in 2012 was due to cancer.[3]

The cost of care will, naturally, increase proportionally. Cancer is indeed big business.

Cancer drugs are extremely expensive - $4000.00 per dose for

Herceptin, one of the main drugs used to treat breast cancer - even though it is

only partially effective, and is known to cause life-threatening heart

problems in some patients. $5500.00 is the physician cost for a one month

supply of

abiraterone, a new drug used for prostate cancer.

So why would we want to flush the drugs down the toilet?

An article published in ASCO Daily News during the annual 2012 American

Society of Clinical Oncology meetings in Chicago, IL written by

Mark J Ratain of the University of Chicago, asks just that question.[4]

An article published in ASCO Daily News during the annual 2012 American

Society of Clinical Oncology meetings in Chicago, IL written by

Mark J Ratain of the University of Chicago, asks just that question.[4]

The author’s point is that there is marked variability in absorption of drug, and therefore in its availability to the body, for at least one third of the oral chemotherapeutic agents currently being prescribed.[5] Abiraterone, mentioned above, is one of those drugs. It shows a 10-fold variation in absorption, depending on whether it is taken without or with food, and shows better absorption when taken with a fatty meal.

So why does the package insert and dosing instructions recommend that it be taken on an empty stomach? Because that is what the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends, according to an editorial written in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2010.[6]

In that editorial, the authors (one of whom was affiliated with the FDA)

expressed concern about the potential for high intra-individual variability

in cancer patients resulting from variability in oral intake secondary

to disease or concurrent medications, suggesting a preference for labeling

drugs under fasting conditions, even if bioavailability were markedly

increased by food.

In that editorial, the authors (one of whom was affiliated with the FDA)

expressed concern about the potential for high intra-individual variability

in cancer patients resulting from variability in oral intake secondary

to disease or concurrent medications, suggesting a preference for labeling

drugs under fasting conditions, even if bioavailability were markedly

increased by food.

This author writes: “Although individual patients can have a medication’s dose titrated to the desired effect, it is rarely feasible for an individual patient to adjust his or her dose by administration with or without food to achieve consistent bioavailability and systemic exposure. The volume and timing of a meal, caloric content, liquid content, fat versus carbohydrate content, temperature, and physical composition can all produce unpredictable variability in the magnitude of a food effect from dose to dose.”

Was that perfectly clear?

Translation: patients cannot possibly understand what we mean by a “fatty meal”, nor can they be counted on to consult with their physician if they are unable to consume said fatty meal (presumably because of nausea resulting from other chemotherapeutic agents also prescribed). Therefore patients should take the highest possible dose, with the least effective absorption, in order to be consistent with FDA recommendations - and, incidentally, with pharmaceutical industry profitability.

What a knock! The conclusion of the Jain article questions the FDA’s recommendation: “Drug labeling patterns with respect to food-drug interactions observed with oncology drugs are in contradiction with fundamental pharmacologic principles, as exemplified in the labeling of non-oncology drugs.”

In a word: the FDA needs to put its money where its mouth is - i.e. needs to be consistent with principles of pharmacology, not with principles of profitability.

So what is the alternative?

At the Arizona Center for Advanced Medicine, we use a combination of modalities to treat cancer.

We use diet - primarily vegetable based (to avoid the glutamine which cancer cells use preferentially for their little cancer cell nutrition), free of chemicals and anything which might be inflammatory (sugars, large amounts of animal protein, sodas, chemicals, preservatives, estrogen-mimicking compounds like BPA, etc).

We use lifestyle changes - even a little bit of exercise is helpful to get the energies moving again.

We use alternative cancer-treating medications and supplements - things like high dose ascorbic acid, lipoic acid, DMSO, glutathione, unltra-violet blood irradiation, vitamin B17, and others.

We use energetic treatments to help restore the body’s information systems to their original template.

And we use Insulin Potentiated Chemotherapy, Low Dose (IPT-LD™) to deliver appropriate chemotherapeutic drugs to rapidly metabolizing cancer cells, sparing the normally metabolizing cells in the rest of the body. Chemotherapy is delivered in lower dose, resulting in fewer side effects and higher quality of life than standard chemotherapy, without any decrease in effectiveness.

We do all of the above in an atmosphere of love and acceptance. Each of us brings who we are to the table. Each of us needs to be accepted, with all our good points and all our warts. Only through acceptance and love is change possible.

We all have the chance to love ourselves with all our faults.

The choice is ours.

The cost of care will, naturally, increase proportionally. Cancer is indeed big business.

Cancer drugs are extremely expensive - $4000.00 per dose for

Herceptin, one of the main drugs used to treat breast cancer - even though it is

only partially effective, and is known to cause life-threatening heart

problems in some patients. $5500.00 is the physician cost for a one month

supply of

abiraterone, a new drug used for prostate cancer.

So why would we want to flush the drugs down the toilet?

An article published in ASCO Daily News during the annual 2012 American

Society of Clinical Oncology meetings in Chicago, IL written by

Mark J Ratain of the University of Chicago, asks just that question.[4]

An article published in ASCO Daily News during the annual 2012 American

Society of Clinical Oncology meetings in Chicago, IL written by

Mark J Ratain of the University of Chicago, asks just that question.[4]

The author’s point is that there is marked variability in absorption of drug, and therefore in its availability to the body, for at least one third of the oral chemotherapeutic agents currently being prescribed.[5] Abiraterone, mentioned above, is one of those drugs. It shows a 10-fold variation in absorption, depending on whether it is taken without or with food, and shows better absorption when taken with a fatty meal.

So why does the package insert and dosing instructions recommend that it be taken on an empty stomach? Because that is what the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends, according to an editorial written in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2010.[6]

In that editorial, the authors (one of whom was affiliated with the FDA)

expressed concern about the potential for high intra-individual variability

in cancer patients resulting from variability in oral intake secondary

to disease or concurrent medications, suggesting a preference for labeling

drugs under fasting conditions, even if bioavailability were markedly

increased by food.

In that editorial, the authors (one of whom was affiliated with the FDA)

expressed concern about the potential for high intra-individual variability

in cancer patients resulting from variability in oral intake secondary

to disease or concurrent medications, suggesting a preference for labeling

drugs under fasting conditions, even if bioavailability were markedly

increased by food.

This author writes: “Although individual patients can have a medication’s dose titrated to the desired effect, it is rarely feasible for an individual patient to adjust his or her dose by administration with or without food to achieve consistent bioavailability and systemic exposure. The volume and timing of a meal, caloric content, liquid content, fat versus carbohydrate content, temperature, and physical composition can all produce unpredictable variability in the magnitude of a food effect from dose to dose.”

Was that perfectly clear?

Translation: patients cannot possibly understand what we mean by a “fatty meal”, nor can they be counted on to consult with their physician if they are unable to consume said fatty meal (presumably because of nausea resulting from other chemotherapeutic agents also prescribed). Therefore patients should take the highest possible dose, with the least effective absorption, in order to be consistent with FDA recommendations - and, incidentally, with pharmaceutical industry profitability.

What a knock! The conclusion of the Jain article questions the FDA’s recommendation: “Drug labeling patterns with respect to food-drug interactions observed with oncology drugs are in contradiction with fundamental pharmacologic principles, as exemplified in the labeling of non-oncology drugs.”

In a word: the FDA needs to put its money where its mouth is - i.e. needs to be consistent with principles of pharmacology, not with principles of profitability.

So what is the alternative?

At the Arizona Center for Advanced Medicine, we use a combination of modalities to treat cancer.

We use diet - primarily vegetable based (to avoid the glutamine which cancer cells use preferentially for their little cancer cell nutrition), free of chemicals and anything which might be inflammatory (sugars, large amounts of animal protein, sodas, chemicals, preservatives, estrogen-mimicking compounds like BPA, etc).

We use lifestyle changes - even a little bit of exercise is helpful to get the energies moving again.

We use alternative cancer-treating medications and supplements - things like high dose ascorbic acid, lipoic acid, DMSO, glutathione, unltra-violet blood irradiation, vitamin B17, and others.

We use energetic treatments to help restore the body’s information systems to their original template.

And we use Insulin Potentiated Chemotherapy, Low Dose (IPT-LD™) to deliver appropriate chemotherapeutic drugs to rapidly metabolizing cancer cells, sparing the normally metabolizing cells in the rest of the body. Chemotherapy is delivered in lower dose, resulting in fewer side effects and higher quality of life than standard chemotherapy, without any decrease in effectiveness.

We do all of the above in an atmosphere of love and acceptance. Each of us brings who we are to the table. Each of us needs to be accepted, with all our good points and all our warts. Only through acceptance and love is change possible.

We all have the chance to love ourselves with all our faults.

The choice is ours.

The author’s point is that there is marked variability in absorption of drug, and therefore in its availability to the body, for at least one third of the oral chemotherapeutic agents currently being prescribed.[5] Abiraterone, mentioned above, is one of those drugs. It shows a 10-fold variation in absorption, depending on whether it is taken without or with food, and shows better absorption when taken with a fatty meal.

So why does the package insert and dosing instructions recommend that it be taken on an empty stomach? Because that is what the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends, according to an editorial written in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2010.[6]

In that editorial, the authors (one of whom was affiliated with the FDA)

expressed concern about the potential for high intra-individual variability

in cancer patients resulting from variability in oral intake secondary

to disease or concurrent medications, suggesting a preference for labeling

drugs under fasting conditions, even if bioavailability were markedly

increased by food.

In that editorial, the authors (one of whom was affiliated with the FDA)

expressed concern about the potential for high intra-individual variability

in cancer patients resulting from variability in oral intake secondary

to disease or concurrent medications, suggesting a preference for labeling

drugs under fasting conditions, even if bioavailability were markedly

increased by food.

This author writes: “Although individual patients can have a medication’s dose titrated to the desired effect, it is rarely feasible for an individual patient to adjust his or her dose by administration with or without food to achieve consistent bioavailability and systemic exposure. The volume and timing of a meal, caloric content, liquid content, fat versus carbohydrate content, temperature, and physical composition can all produce unpredictable variability in the magnitude of a food effect from dose to dose.”

Was that perfectly clear?

Translation: patients cannot possibly understand what we mean by a “fatty meal”, nor can they be counted on to consult with their physician if they are unable to consume said fatty meal (presumably because of nausea resulting from other chemotherapeutic agents also prescribed). Therefore patients should take the highest possible dose, with the least effective absorption, in order to be consistent with FDA recommendations - and, incidentally, with pharmaceutical industry profitability.

What a knock! The conclusion of the Jain article questions the FDA’s recommendation: “Drug labeling patterns with respect to food-drug interactions observed with oncology drugs are in contradiction with fundamental pharmacologic principles, as exemplified in the labeling of non-oncology drugs.”

In a word: the FDA needs to put its money where its mouth is - i.e. needs to be consistent with principles of pharmacology, not with principles of profitability.

So what is the alternative?

At the Arizona Center for Advanced Medicine, we use a combination of modalities to treat cancer.

We use diet - primarily vegetable based (to avoid the glutamine which cancer cells use preferentially for their little cancer cell nutrition), free of chemicals and anything which might be inflammatory (sugars, large amounts of animal protein, sodas, chemicals, preservatives, estrogen-mimicking compounds like BPA, etc).

We use lifestyle changes - even a little bit of exercise is helpful to get the energies moving again.

We use alternative cancer-treating medications and supplements - things like high dose ascorbic acid, lipoic acid, DMSO, glutathione, unltra-violet blood irradiation, vitamin B17, and others.

We use energetic treatments to help restore the body’s information systems to their original template.

And we use Insulin Potentiated Chemotherapy, Low Dose (IPT-LD™) to deliver appropriate chemotherapeutic drugs to rapidly metabolizing cancer cells, sparing the normally metabolizing cells in the rest of the body. Chemotherapy is delivered in lower dose, resulting in fewer side effects and higher quality of life than standard chemotherapy, without any decrease in effectiveness.

We do all of the above in an atmosphere of love and acceptance. Each of us brings who we are to the table. Each of us needs to be accepted, with all our good points and all our warts. Only through acceptance and love is change possible.

We all have the chance to love ourselves with all our faults.

The choice is ours.

In that editorial, the authors (one of whom was affiliated with the FDA)

expressed concern about the potential for high intra-individual variability

in cancer patients resulting from variability in oral intake secondary

to disease or concurrent medications, suggesting a preference for labeling

drugs under fasting conditions, even if bioavailability were markedly

increased by food.

In that editorial, the authors (one of whom was affiliated with the FDA)

expressed concern about the potential for high intra-individual variability

in cancer patients resulting from variability in oral intake secondary

to disease or concurrent medications, suggesting a preference for labeling

drugs under fasting conditions, even if bioavailability were markedly

increased by food.

This author writes: “Although individual patients can have a medication’s dose titrated to the desired effect, it is rarely feasible for an individual patient to adjust his or her dose by administration with or without food to achieve consistent bioavailability and systemic exposure. The volume and timing of a meal, caloric content, liquid content, fat versus carbohydrate content, temperature, and physical composition can all produce unpredictable variability in the magnitude of a food effect from dose to dose.”

Was that perfectly clear?

Translation: patients cannot possibly understand what we mean by a “fatty meal”, nor can they be counted on to consult with their physician if they are unable to consume said fatty meal (presumably because of nausea resulting from other chemotherapeutic agents also prescribed). Therefore patients should take the highest possible dose, with the least effective absorption, in order to be consistent with FDA recommendations - and, incidentally, with pharmaceutical industry profitability.

What a knock! The conclusion of the Jain article questions the FDA’s recommendation: “Drug labeling patterns with respect to food-drug interactions observed with oncology drugs are in contradiction with fundamental pharmacologic principles, as exemplified in the labeling of non-oncology drugs.”

In a word: the FDA needs to put its money where its mouth is - i.e. needs to be consistent with principles of pharmacology, not with principles of profitability.

So what is the alternative?

At the Arizona Center for Advanced Medicine, we use a combination of modalities to treat cancer.

We use diet - primarily vegetable based (to avoid the glutamine which cancer cells use preferentially for their little cancer cell nutrition), free of chemicals and anything which might be inflammatory (sugars, large amounts of animal protein, sodas, chemicals, preservatives, estrogen-mimicking compounds like BPA, etc).

We use lifestyle changes - even a little bit of exercise is helpful to get the energies moving again.

We use alternative cancer-treating medications and supplements - things like high dose ascorbic acid, lipoic acid, DMSO, glutathione, unltra-violet blood irradiation, vitamin B17, and others.

We use energetic treatments to help restore the body’s information systems to their original template.

And we use Insulin Potentiated Chemotherapy, Low Dose (IPT-LD™) to deliver appropriate chemotherapeutic drugs to rapidly metabolizing cancer cells, sparing the normally metabolizing cells in the rest of the body. Chemotherapy is delivered in lower dose, resulting in fewer side effects and higher quality of life than standard chemotherapy, without any decrease in effectiveness.

We do all of the above in an atmosphere of love and acceptance. Each of us brings who we are to the table. Each of us needs to be accepted, with all our good points and all our warts. Only through acceptance and love is change possible.

We all have the chance to love ourselves with all our faults.

The choice is ours.